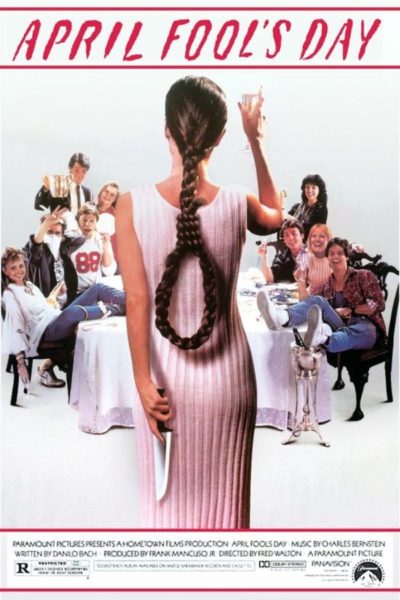

For most of my life, April Fools day would pass me by and I wouldn’t even notice. But, there is always a cause for celebration when you are celebrating with movies, and on April 1st we watch April Fool’s Day (1986). April Fool’s Day is a wonderful little mystery slasher featuring Deborah Foreman of Valley Girl, Real Genius, and a cart load of other films from my 80s childhood. Happy April Fools!

At the last minute we remembered that Killer Party (1986) should also join our celebration. Killer Party was originally going to be called either Fool’s Night or April Fool but was changed when April Fool’s Day was released by Paramount Pictures. Happy April Fools!

April 1st is also when we have estimated Spasmo’s birthday to be. So, Happy Birthday Spasmo!