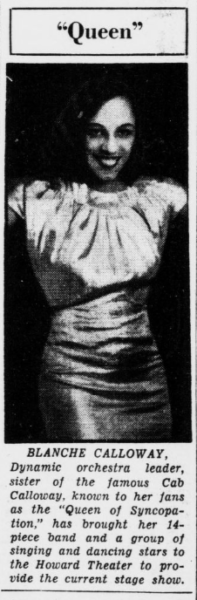

It’s been a while since I worked up an Every Month is ____ History Month post. Truth is, I got rather stalled on Pearl Bailey. The more information I found on her, the more I became completely fascinated, and nothing I found was quite enough. Unlike many other personalities that no-one I know seems to remember, Pearl Bailey wrote quite a bit about her life. I can’t tell you how excited I was to find out she had penned her own memoirs and social commentary. Suddenly, only her own words would do. I acquired a few of her books and, unfortunately, they got added to my to-read shelves. And, that is where the research post ended, until now.

No, I haven’t finished reading her biography (the one I picked up). I have read through Hurry Up America and Spit (1976), and I am currently picking through Pearl’s Kitchen (1973). The song on our Christmas mix, ‘Five Pound Box of Money’ by Pearl Bailey is just too good not to share now, and since I have got enough information for a basic biographical sketch, I figured why keep waiting. I am now a confirmed Pearl Bailey fan. I’m not going to have any trouble revisiting this great lady in another post once I have read about her story in her own words.

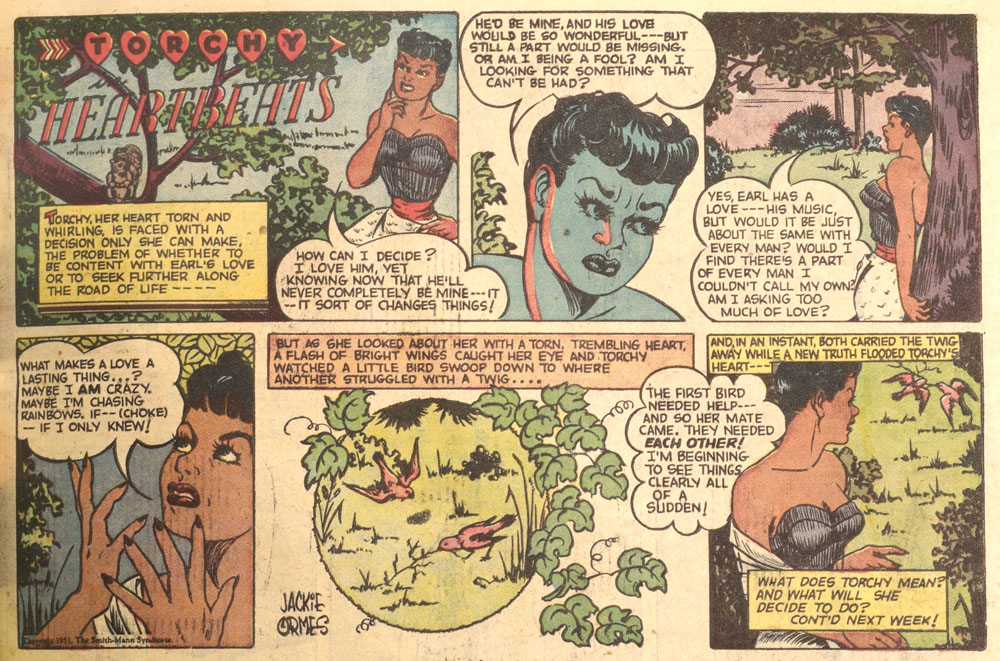

Pearl Baily was born in 1918 in Newport News, Virginia to Reverend Joseph James and Ella Mae Ricks Bailey (Pearl Bailey, 2022). Her brother, Bill Bailey was well known on the vaudeville stage. In a later article, Bailey recounted how she stumbled accidentally into show business by way of what sounded like a sibling spat. She had been sent to the theater to fetch her brother, who was rehearsing his dance act. He brushed her off and sent her home, so she returned, entered, and won the amateur contest that night. She was just fifteen (Pearl Bailey is serious about ambition to teach, 1956). After some time on vaudeville stages and touring the country with the USO during WWII, she made her Broadway debut in St. Louis Woman in 1946 (Pearl Bailey, 2022) to excited and complimentary reviews (Pearl Bailey’s easy style clicks on Broadway, 1946).

“The way I sing is the way I live,” Miss Bailey says…”What I do is like telling a story to music, it’s got to be something that brings a chuckle. The audience enjoys it because it tells of things they know.”

– Pearl Bailey (Pearl Bailey’s easy style clicks on Broadway, 1946)

Early on, she would describe herself as a writer when speaking with reporters and critics. Throughout a very successful career entertaining on stage, through which she was often featured in newspapers, she would carefully craft and plan her shows based on her projections of what the audience would be (Pearl Bailey’s next role, 1956). By 1956 she declared a desire to follow her long time dream of becoming a teacher, taking classes at UCLA towards that ambition (Pearl Bailey is serious about ambition to teach, 1956). She would later earn a degree in theology from Georgetown University, but before this she published several books (Pearl Bailey, 2022):

- The Raw Pearl (1968)

- Talking to Myself (1971)

- Pearl’s Kitchen (1973)

- Hurry Up America and Spit (1976)

- Between You and Me (1989)

Somewhat satisfyingly, her achievements and greatness were awarded many times over during her lifetime. She was appointed special ambassador to the United Nations by President Gerald Ford; she received a Special Tony Award for the title role in the all-black production of Hello, Dolly!; she won a Daytime Emmy award; she was the first African-American to receive the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award; she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom; and she was awarded the Bronze Medallion, the highest award conferred upon civilians by New York City (Pearl Bailey, 2022). Pearl Bailey died at the age of 72 from arteriosclerosis (Pearl Bailey, 2022).

There is so much more that I haven’t covered here and, I promise, I will get to it. But for now, enjoy a little Christmas:

References

- It happened in New Jersey The Miami times. [volume] (Miami, Fla.), 04 Oct. 1952. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83004231/1952-10-04/ed-1/seq-6/>

- Pearl Bailey (2022) Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pearl_Bailey

- Pearl Bailey Foils Thugs. The Detroit tribune. (Detroit, Mich.), 30 Sept. 1950. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92063852/1950-09-30/ed-1/seq-19/>

- Pearl Baily in Fight at Nightclub. The Ohio daily-express. (Dayton, Ohio), 25 March 1950. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn88077226/1950-03-25/ed-1/seq-1/>

- Pearl Bailey in Review. The Detroit tribune. (Detroit, Mich.), 23 Oct. 1948. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92063852/1948-10-23/ed-1/seq-13/>

- Pearl Bailey is serious about ambition to teach. Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 20 May 1956. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1956-05-20/ed-1/seq-99/>

- Pearl Bailey tells of child adoption. The Detroit tribune. (Detroit, Mich.), 08 Dec. 1956. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92063852/1956-12-08/ed-1/seq-8/>

- Pearl Bailey Tired. The Detroit tribune. (Detroit, Mich.), 13 Jan. 1951. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn92063852/1951-01-13/ed-1/seq-11/>

- Pearl Bailey to marry white drummer with Duke Ellington’s band. Jackson advocate. [volume] (Jackson, Miss.), 22 Nov. 1952. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn79000083/1952-11-22/ed-1/seq-1/>

- Pearl Bailey’s easy style clicks on Broadway. The daily bulletin. [volume] (Dayton, Ohio), 08 July 1946. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84024221/1946-07-08/ed-1/seq-2/>

- Pearl Bailey’s next role: dude ranch proprieter. Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 18 Jan. 1956. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1956-01-18/ed-1/seq-60/>

- Singer Pearl Baily beaten in night club. Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 16 Sept. 1952. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1952-09-16/ed-1/seq-9/>