The people we know as the Pilgrims were far from the first Europeans to set foot on or colonize the land later incorporated into the United States. Explorers, fishermen, fur traders, missionaries, and treasure seekers had all been here. European and Native American interactions prior to and contemporary with that of the Pilgrims ranged between aggressive and friendly. However generously the native people sometimes viewed European invaders, Europeans arrived to exploit natural resources, claim land that belonged to native peoples, and bring disease against which the native population had no immunity.

By uncredited – Baharris.org, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38941602

By The German Kali Works, New York – Bricker, Garland Armor. The Teaching of Agriculture in the High School. New York: Macmillan, 1911. Page 112., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6767475

By Sculptor Cyrus E. Dallin (1861-1944). – Self-photographed, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4143607

At times, Europeans came to enslave. Tisquantum, often called Squanto, was kidnapped by an English explorer who took him to Spain to be sold into slavery. He was ‘bought’ by Spanish monks whose work included educating and evangelizing those they perceived as lesser. When Tisquantum finally escaped and returned to his home lands, by way of England, he found that his whole tribe had been killed by an epidemic infection likely brought to the land by the rats of European ships. Tisquantum was the last of the Patuxets.

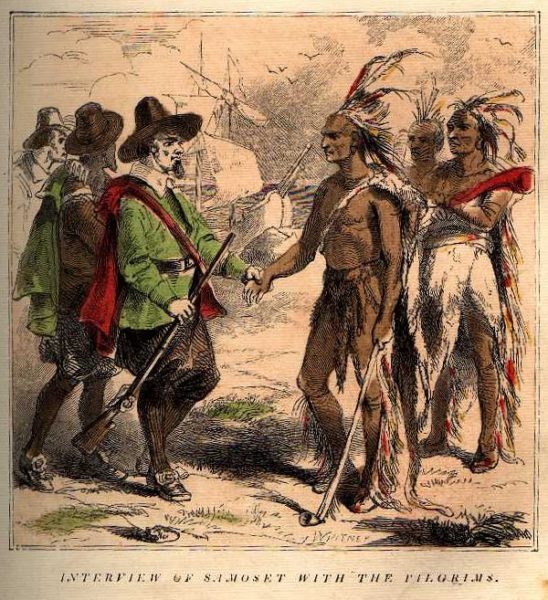

Tisquantum was living among the Pokanoket tribe, part of a confederation of tribes called the Wampanoag, when the Pilgrims first emerged from wintering on the Mayflower. Samoset, an Abenaki Sagamore was also staying with the Pokanoket tribe at the time. Samoset had learned the English language from fishermen who frequented the waters of Maine, near the lands of the Abenaki people. He approached the Pilgrims to initiate trade relations, and would later arrange the meetings of the Pilgrim colonists with Tisquantum and Ousamequin, also known as Massasoit.

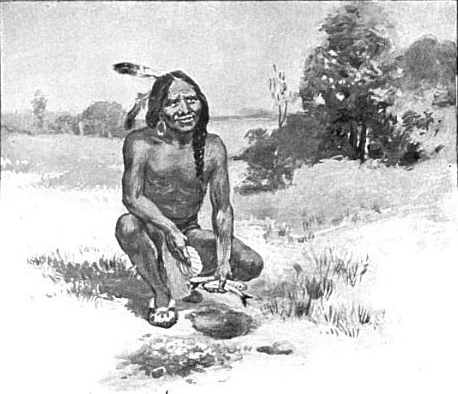

Ousamequin, Great Sachem of the Wampanoag, had watched his people weakened by epidemic and become vulnerable to attacks by the Narragansetts, a neighboring tribe. Because of this, Ousamequin sought out an early alliance with the new settlers in the hopes it would protect his tribe. The alliance between the Wampanoag and the Pilgrims would last for fifty years, despite colonial expansion, the continuing spread of disease, exploitation of Wampanoag land, and dissent on both sides. Early on, Ousamequin sent Tisquantum to live among the Pilgrims. Tisquantum would teach the new arrivals how to fish, how to identify and avoid poisonous vegetation, how to plant corn, and how to extract sap from Maple trees. The teachings and assistance he provided, perhaps in spite of his previous experiences with Europeans, saved the Pilgrims from starvation.

In November of 1621, after surviving nearly a year in a new land and reaping a decent harvest, the Governor of the Pilgrim colony invited Ousamequin to a celebratory feast and Thanksgiving. Over 90 Wampanoag and ally Native American men joined the 50 or so Pilgrim men for three days of feasting and games. The feast would be much different than the Thanksgiving dishes set on modern tables. It likely included corn, venison, duck and other game, cod, shellfish, and eel.

That three day feast in 1621 was far from the first Thanksgiving in the New World. For the Pilgrims, it was likely informed by the long history of harvest festivals in the Old World. Celebrating a successful harvest with feast and festival is a tradition that can be traced back to ancient Roman and early European communities. Harvest festivals and feasting to give thanks for good crops and also for surviving a winter were also practiced among Native Americans for thousands of years. Perhaps it was during one of these celebrations that the Seloy tribe shared their harvest with Spanish Settlers in St. Augustine in 1565. This earlier celebration would be accompanied by a mass of Thanksgiving, performed by the local missionary.

Though the alliance between the Pilgrim colonists and the Wampanoag lasted longer than any other such alliance, the relationship between these two communities started to deteriorate after Ousamequin died in 1661 and his son Wamsutta died shortly after while visiting the Pilgrims in 1662. Wamsutta’s successor, Metacomet arranged a defensive coalition to protect tribes of the area from further encroachment and exploitation. This was both a symptom of and kindling for increased tensions between the two communities. A skirmish between colonists and Native Americans in 1675 was one of several events that marked the end of peace between the two populations. The English colonists would call Metacomet ‘King Philip’ and the years of fighting that followed would be called ‘King Philip’s War.’

The following wars and broken treaties between European colonists and Native American tribes became a systematic dismantling, by the United States, of a complex political and cultural web of hundreds of Native American tribes. It became genocide. The fairy tale story that kids in the US hear of how the Pilgrims met with friendly Native Americans and shared the bounty of their first harvest in the New World is a dangerously rosy and incomplete picture of early colonist and Native American relations. This is why some Native American groups have commemorated Thanksgiving as a National Day of Mourning since 1970. A Thanksgiving harvest feast and days of celebration may have been shared between the Pilgrims and the Wampanoag, but when we remember those days it should be with full acknowledgement of what came before and after.

References

- Bugos, Claire (2019) The Myths of the Thanksgiving Story and the Lasting Damage They Imbue. Smithsonian Mag. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/thanksgiving-myth-and-what-we-should-be-teaching-kids-180973655/

- Inglish, Patty (2016) Native American Harvest Feasts Before Thanskgiving. Owlcation. https://owlcation.com/humanities/Native-American-Harvest-Feasts

- Kershner, Ellen. (2020) History of American Thanksgiving. World Atlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-history-of-american-thanksgiving.html

- Lizleafloor (2019) American Thanksgiving Origins and Roots in the Old World. Ancient Origins. https://www.ancient-origins.net/history-ancient-traditions/american-tradition-thanksgiving-harvest-festival-roots-old-world-004694

- Massasoit (2020) wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Massasoit

- Samoset (2020) Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samoset

- Schumer, Lizz (2020) The True, Dark History Behind Thanksgiving: It wasn’t all peace and harmony between the Pilgrims and Native Americans. Good Housekeeping. https://www.goodhousekeeping.com/holidays/thanksgiving-ideas/a33446829/thanksgiving-history/

- Squanto (2020) Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Squanto

- “Thanksgiving 2020” (2020) History.com. https://www.history.com/topics/thanksgiving/history-of-thanksgiving