Introduction

Any discussion on the origin of the giallo, whether the discussion is concerned with the literature or the film phenomenon, will most likely begin with an explanation that the giallo took its name from the yellow book covers used by Mondadori to color code their mystery novel publications (Pieri, 2011; Koven, 2006; Needham, 2002). Eventually, giallo became a term used for any type of detective fiction, story with a mystery element, or intrigue. Mikel Koven would coin it a “metonym for the entire mystery genre (2006 p2-3).” Initially, between WWI and WWII, the stories were imported from the UK, America, and France. The foreignness helped to distance the stories of crime and murder from Italian readers while also becoming so attractive an element that Italian authors began to adopt anglicized pseudonyms to put their locally produced work on even footing with the popular imports (Pierri, 2011; Needham, 2002). Italian writers of the giallo faced another hurdle in competing with the foreign imports in the strict oversight and censorship in the Fascist regime pre WWII for their production of what was considered low brow literature. This label of ‘low brow’ followed the giallo from literature to film when the movies rose as a genre in the 60s and 70s, sometimes considered a component of a larger movement in Italian Fantasy Cinema that included horror (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996). The giallo in film has been popularly defined by its characteristics, by time period, and by driving personalities. It has been said to be an “auteurist domain,” defined by the directorial names that made the most memorable examples of the genre; defined by Argento (Heller-Nicholas, 2012; Palmerini & Mistretts, 1996). However, similar to the debate over the rigid, proscribed, and repetitive structure of crime fiction literature giving way, through that very repetition, to a dynamic and flexible reimagining of the genre (Maher & Pezzotti, 2017), the cinematic giallo has also been described as having “an inherently ambivalent form (Koven, 2010 p144)”. Despite the giallo’s formulaic narratives and repetitious plot elements, the genre can seem even less definable in film than in literature, and may represent a cultural exchange that only adds to its fluidity and timelessness (Heller-Nicholas, 2012). As Gary Needham thoroughly points out:

Any discussion on the origin of the giallo, whether the discussion is concerned with the literature or the film phenomenon, will most likely begin with an explanation that the giallo took its name from the yellow book covers used by Mondadori to color code their mystery novel publications (Pieri, 2011; Koven, 2006; Needham, 2002). Eventually, giallo became a term used for any type of detective fiction, story with a mystery element, or intrigue. Mikel Koven would coin it a “metonym for the entire mystery genre (2006 p2-3).” Initially, between WWI and WWII, the stories were imported from the UK, America, and France. The foreignness helped to distance the stories of crime and murder from Italian readers while also becoming so attractive an element that Italian authors began to adopt anglicized pseudonyms to put their locally produced work on even footing with the popular imports (Pierri, 2011; Needham, 2002). Italian writers of the giallo faced another hurdle in competing with the foreign imports in the strict oversight and censorship in the Fascist regime pre WWII for their production of what was considered low brow literature. This label of ‘low brow’ followed the giallo from literature to film when the movies rose as a genre in the 60s and 70s, sometimes considered a component of a larger movement in Italian Fantasy Cinema that included horror (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996). The giallo in film has been popularly defined by its characteristics, by time period, and by driving personalities. It has been said to be an “auteurist domain,” defined by the directorial names that made the most memorable examples of the genre; defined by Argento (Heller-Nicholas, 2012; Palmerini & Mistretts, 1996). However, similar to the debate over the rigid, proscribed, and repetitive structure of crime fiction literature giving way, through that very repetition, to a dynamic and flexible reimagining of the genre (Maher & Pezzotti, 2017), the cinematic giallo has also been described as having “an inherently ambivalent form (Koven, 2010 p144)”. Despite the giallo’s formulaic narratives and repetitious plot elements, the genre can seem even less definable in film than in literature, and may represent a cultural exchange that only adds to its fluidity and timelessness (Heller-Nicholas, 2012). As Gary Needham thoroughly points out:

“One interesting point about the giallo in its cinematic form is that it appears to be less fixed as a genre than its written counterpart. The term itself doesn’t indicate, as genres often do, an essence, a description or a feeling. It functions in a more peculiar and flexible manner as a conceptual category with highly movable and permeable boundaries that shift around from year to year… (2002)”

What follows is an exploration into the phenomenon of and discourse on the cinematic giallo, as it is intrinsically linked to giallo literature and to the unique historical environment in which it evolved, to determine what, if any, are the defining elements that make a film a giallo. Perhaps like it’s literature forebears, the giallo’s blending of characteristics from different genres creates “dynamic conceptual structures” that cannot be defined without allowing for blurred boundaries (Maher & Pezzotti, 2017 p9).

Giallo and its literary roots

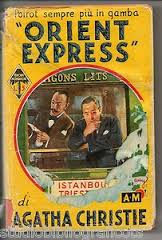

After Mondadori launched their ‘yellow’ book series in 1929 as a vehicle to import the works of Agatha Christie, Edgar Wallace, Georges Simenon, Raymond Chandler, and more, a follow-up to a previously successful campaign of color coding their romance offerings in blue, other publishers followed suit, using giallo to give a uniquely Italian context to a literary genre (Koven, 2010). The adjective giallo even became a generic label for detective fiction, mystery, and crime. Exotic locales of France, America, and England inspired Italian xenophilia and left an indelible mark on the genre (Weller, 2012; Pieri, 2011; Koven, 2010; Somigli, 2005). Also shaping giallo development were the proscriptive theorizations of what detective fiction is and should be, like “Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories” by S.S. Van Dine, first published in 1928, and Raymond Chandler’s 1944 essay “The Simple Art of Murder.” Critical of the tired cliches that permeated the genre, both essays denounce characteristics common in detective fiction while still providing only a narrow path for what would constitute a valuable detective novel. As Van Dine himself states: “Detective stories …have very definite laws — unwritten, perhaps, but none the less binding: and every respectable and self-respecting concocter of literary mysteries lives up to them (Van Dine, 1928).” The preoccupation with separating the wheat from the chaffe, the ‘good’ detective novel from the ‘bad,’ in both Van Dine’s essay and Chandler’s indicates a larger argument, and perhaps label, on detective fiction as ‘low-brow.’ Chandler would call most detective stories contrived and bemoan the publisher’s ‘lack of discernment’ in publishing new novels to feed the hungry reading populous, while he benefited from the same audience hunger that drove the need for greater output.

This label of ‘low-brow’ and argument on what made a good detective story would travel to Italy along with the glut of detective novels that Van Dine and Chandler criticized. Augusto De Angelis, an influential early Italian detective novelist, would likewise suggest that a higher polished giallo existed among the trash that, he said, should be burned in mass. However, his definition of what composed a ‘good’ giallo, was markedly different than Van Dine’s and Candler’s. In his “Conferenza Sul Giallo (in tempi neri),” originally published in 1939 as the introduction to Le Sette Picche Doppiate, he quotes Dorothy Sayers, agreeing with her that the detective novel should be a frenetic, calculated, tense, and vibrant literature of escape (De Angelis, 1980). Leonardo Sciascia, another founding father of giallo, identifies a higher and lower form of giallo: one that is worthy of study and one for the “careless consumption by the masses (Sciascia, 1954).” However, in a break from the ordered and puzzle-like detective story described by Van Dine, Sciascia, in his essay “Appunti Sul ‘giallo’,” elevates instead “narration marked by an uninterrupted emotional current to which the reader abandons himself without the possibility of intellectual re-enactments (1954).” Similar to their American counterparts, De Angelis and Sciascia felt driven to separate the good from the bad detective novel, however the narratives they called for were less prescriptive and more emotionally driven than the laundry lists concocted by authors like Van Dine. The self-reflective and critical arguments by detective novelists, both Italian and other, did little to change scholarly regard for the genre as it has only recently been given any serious consideration or viewed as valuable social critique (Eckert, 2016; Santovetti, 2012).

Censorship by the Fascist government of Italy would put an authoritarian seal on the classification of giallo as ‘low-brow’ and corrupt; leading fascist film-makers to mostly overlook the genre as potential meat for their cinematic projects (Koven, 2006). Strict censorship rules would also enforce the foreign aspects of the giallo, as any perceived critique of the fascist regime, or the artificial and purported idyllic Italian society that existed under fascism, would not make it to publication, however, stories of murder and violent crime happening in far-flung and troubled locales like the United States were acceptable as long as they conformed to literary bans (Pieri, 2011; Somigli, 2005). Foreign locations, foreign police structures, foreign inheritance laws all lent an otherness to the imported giallo that authors like de Angelis railed against. Described as the ‘finest Italian detective novelist of his generation’ and ‘il maggior autore poliziesco’ of the period (Dunnet, 2011; Somigli, 2005), de Angelis wrote about how he yearned for an Italian detective story. He would say,

“Everything is missing from us, in real life, to be able to devise a detective story of the American or English type. The detectives are missing, the policemen are missing, the gangsters are missing, even the fragile heirs are missing and the old powerful money and intrigue willing to be killed. There is no shortage [of] crimes. Tragedies are not lacking (De Angelis, 1980).”

De Angelis would also be one of the first, and most successful in his day, to construct an Italian detective fiction, with an Italian Commissario. His meditations on the genre included affirmations of the detective novel as a reflection of reality and the stresses and contradictions of the period. Like Sciascia after him, de Angelis would eschew the proscribed and puzzle-like detective narrative for stories more concerned with the motivation behind the act (Somigli, 2005). De Angelis’ Commissario would delve below the surface to unearth the politics, myths, and history involved that resulted in the sundry clues other detectives may simply use to solve a case. The result would be a rich and multi-faceted “social analysis of contemporary Italian reality;” one that tied fiction to the “important phenomena of present-day life: migration, globalization, transnationalism, and the complexities arising from the need to balance multiple cultures in a context of shifting and changing geopolitical boundaries (Wilson, 2017 p127).”

The literary giallo would become a story of the subsoil, of humanity, the foreign or other, vision, perception, punishment and justice. It would at once embrace punishment of the criminal, triumph of good over evil, while at the same time admiring the villain who could break through the taboos that imprisoned society. It celebrated a “joy of ambivalence (Sciascia, 1954).” Though the promise of a giallo is a crime punished, and the guilty discovered (De Angelis, 1980), by Umberto Eco’s 1980 Il nome della rosa (The Name of the Rose), giallo writers were conveying the shifting and fragmented society they lived within through uncertain narratives where the villain may not be caught, the evil may not be punished, and the detective may fail (Cicioni, 2013; Weller, 2012). This uncertainty and ambivalence would be transcribed to the cinematic medium and exported in the 60s and 70s to the very same countries that fed the Mondadori publishing venture pre WWII. Like the English thriller, to which it contributed, the giallo television program or film would be marked by mutability where characters were constantly shifting roles, where truth becomes lies, and nothing is as it seems (Hutchings, 2009 p68).

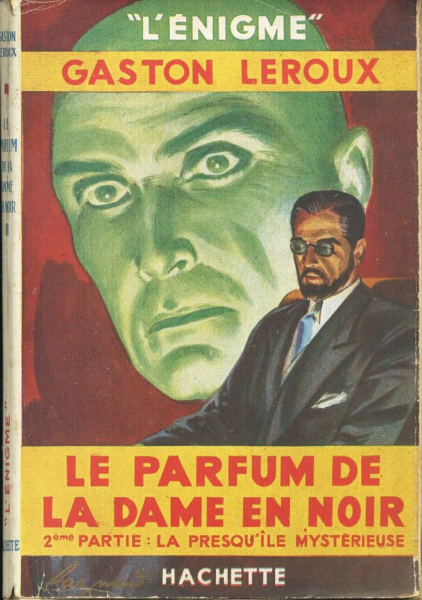

The term giallo itself alludes to the literary, having been established by Mondadori as a literary genre, and viewers often approach films in a similar way to literary texts (Koven, 2006). Beyond this tie of the genre, several giallo films wholly or partly depend on giallo literature. The Perfume of the Woman in Black directly references Gaston Leroux’s novel La Parfum de la dame en noir and draws several connections to the text of Alice and Wonderland (Heller-Nicholas, 2012). Edgar Wallace’s work is referenced in Dario Argento’s Cat O Nine Tails and The Bird With the Crystal Plumage to the extent that the films were marketed in Germany as based on novels by Wallace’s son (Koven, 2006). Agatha Christie and Edgar Allen Poe can be found in Concerta per un pistola (The Weekend Murders), Cinque Bambole per la luna d’agostso (Five Dolls for an August Moon), Sette note in nero (Seven Notes in Black), and Due Occhi Diabolici (Two Evil Eyes) (Needham, 2002). La ragazza che Sapeva Troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much), itself regarded the first giallo by some, follows a female fan of the murder mystery novel, and in Tenebrae author Peter Neal, writer of murder mystery novels, becomes involved in the investigation of a serial killer who is inspired by his stories (Needham, 2002). Even those gialli that do not directly reference literature may owe some of their essense to the written word. Umberto Lenzi, director of giallo films, dedicated himself to the thriller because of his passion for and involvement in giallo literature; Lenzi authored no.1811 of the Mondadori detective series, La Quinta Vittima, which later won an award in 1983. Lamberto Bava similarly credited reading a great deal to his success directing horror films (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996). Defining what it means to be giallo in cinema, then, must include consideration of what it means to be giallo in literature.

The term giallo itself alludes to the literary, having been established by Mondadori as a literary genre, and viewers often approach films in a similar way to literary texts (Koven, 2006). Beyond this tie of the genre, several giallo films wholly or partly depend on giallo literature. The Perfume of the Woman in Black directly references Gaston Leroux’s novel La Parfum de la dame en noir and draws several connections to the text of Alice and Wonderland (Heller-Nicholas, 2012). Edgar Wallace’s work is referenced in Dario Argento’s Cat O Nine Tails and The Bird With the Crystal Plumage to the extent that the films were marketed in Germany as based on novels by Wallace’s son (Koven, 2006). Agatha Christie and Edgar Allen Poe can be found in Concerta per un pistola (The Weekend Murders), Cinque Bambole per la luna d’agostso (Five Dolls for an August Moon), Sette note in nero (Seven Notes in Black), and Due Occhi Diabolici (Two Evil Eyes) (Needham, 2002). La ragazza che Sapeva Troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much), itself regarded the first giallo by some, follows a female fan of the murder mystery novel, and in Tenebrae author Peter Neal, writer of murder mystery novels, becomes involved in the investigation of a serial killer who is inspired by his stories (Needham, 2002). Even those gialli that do not directly reference literature may owe some of their essense to the written word. Umberto Lenzi, director of giallo films, dedicated himself to the thriller because of his passion for and involvement in giallo literature; Lenzi authored no.1811 of the Mondadori detective series, La Quinta Vittima, which later won an award in 1983. Lamberto Bava similarly credited reading a great deal to his success directing horror films (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996). Defining what it means to be giallo in cinema, then, must include consideration of what it means to be giallo in literature.

Giallo in time and space

Despite the overwhelming foreign imports, Italian crime fiction dates back to the late 1900s, with Emilio De Marchi’s 1888 Il cappello del prete identified as the first psychological murder story. The genre developed and grew despite restrictions of the fascist regime and pressures exerted upon society over an intense period of change (Cicioni, 2013; Somigli, 2005). Many novels from the golden age are situated “in a period in which conventional gender roles have been challenged by both war time conditions and experiences and subsequent economic changes and in which attitudes to sexual activity and to sexuality have been similarly shaken up (Burnes, 2011 p36).” This sexual and economic upheaval was not unique to Italy, nor to literature. Similarly, Italian cinematic gialli influenced and were influenced by international interests beyond Italy, and existed in parallel to other cinematographic movements like the German krimi and English thriller (Koven, 2006). The English thriller, especially within a subset of thrillers referred to as ‘women in peril,’ played on anxieties over shifting gender roles with their focus on the expression of female fear. This focus, also common to gialli, highlighted the inherent dysfunction in heterosexual relationships. Though obviously focused on women as victims instead of heroes, these films did not elevate men in any heroic way. In ‘women in peril’ films, men were often the suspects, villains, and unreliable or untrustworthy love interests (Hutchings, 2009).

As part of a larger rise in Italian fantasy cinema or horror, the cinematic giallo has been said to follow an initial Gothic period from 1956 to 1966; the modern giallo from 1970 to 1982 (Brown, 2012) is said to peak in the early 70s (Smith, 1999). Yet the first cinematic giallo is widely discussed as either La Ragazza che Sapeva Troppo (The Girl Who Knew Too Much), directed by Mario Bava in 1962 (Smith, 1999), or Ossessione (Obsession), directed by Luchino Visconti in 1943 and based on the novel The Postman Always Rings Twice by James Cain (Koven, 2006; Wikipedia, 2018). The early dates of these two films would seem to indicate that the period for the ‘modern giallo’ is not so easily defined after all. Not often included in discussion is Giallo, the 1934 thriller comedy based on a play by Edgar Wallace. Notable for being based on the writings of an imported giallo author and made in a time overshadowed by fascist censorship, Giallo has the beginnings of themes that become common in giallo cinema that follows: the untrustworthy love interest and unreliable perception of the main character. The American slasher is said to either be inspired by or to revive the genre, but giallo cinema scholars and authors like Mikel Koven, Adrian Luther-Smith, and Richard Schmidt agree that the slasher rose after the giallo ended (2006; 1999; 2015). It’s worth mentioning that, as Peter Hutchings pointed out, the term giallo was not used outside of Italy for much of the time considered to be the golden age of cinematic gialli. Most often exported gialli were marketed as thrillers or whatever other term was most common to their international audience (2009). This creates a couple of questions: 1.) can a genre, the description of which was translated for international audiences, that involved and influenced cinema from countries other than it’s own, actually be pinned down to a location? And 2.) can a genre so linked to an Italian concept that is alive, pervasive, and has grown to be timeless actually be pinned down to a specific time frame? Giallo literature is alive and vital in Italy today, displaying a longevity in popular culture despite an unstable publishing market (Bolondi, 2017; Wikipedia Italia, 2018). Even de Angelis’ question of whether a genre is created by a generation or a generation is created by a genre has implications as to whether a genre can be wholly defined by time (1980). Drivers of the genre also do not agree. Aristide Massaccesi, a prolific film producer, director and cinematographer of horror films later known as Joe D’Amato, would say of fantasy cinema that it was a timeless genre and a “mainstay in the history of the cinema (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996).” Yet, Dardano Sacchetti, an Italian screenwriter of the horror genre would say of fantasy cinema that “it doesn’t exist. With Mario Bava and Riccardo Freda there was an initial attempt to create something valid, then came Margheriti and Fulci and the qualitative standard dropped a few points. The Italian cinema has never believed in Dario Argento either…Our critics are bizarre: they criticize Italian horror films and then praise American genre films (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996 p123).” These dissenting opinions seem to echo the essays of giallo and American Detective novelists who keenly felt the categorization of their work as ‘low brow,’ along with the desire to argue this categorization by delineating good from bad. While a notable continuing trend, this drive to explain itself in terms of value does little to explain the characteristics and components that define a giallo other than emphasize the timelessness of genre.

Giallo of Italian-ness and Otherness

The giallo film is one of escapism, like its literary counterpart. Unlike its literary counterpart, it has been said that the giallo film, primarily, was not meant for consumption outside of Italy. Mikel Koven would describe the giallo as vernacular cinema (2006), or that which relates to the language and culture enjoyed by ordinary people in a specific region. As vernacular cinema it is a vision of change in Italian culture of the time, of sexuality, increased violence, and women’s independence (Koven, 2006). Tom Savini, actor, director, and special effects artists for horror films, would call upon an Italian colloquialism: “what did Italy produce after 500 years of the Medici and various conflicts and wars? – Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo and Fine Art. What came out of a country like Switzerland where there has never been a conflict because they are always neutral? – Cuckoo clocks” (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996 p133). Italian creativity and art is born from Italian conflict; it is not surprising then, that a genre grown from a desire to embrace Italian-ness would be thoroughly imbued with local knowledge, stereotypes, violence, and debates on gender, identity, racism, and sexuality (Maher, 2016; Maher & Pezzotti, 2017). However, this view does not take into consideration the many giallo that were products of international collaboration; made, not only by two or more national production groups but, for multiple national audiences at the same time. Giallo literature, as crime fiction, crossed the original boundaries layed out for it and absorbed themes of other genres as it reflected on legality, responsibility, the society, and its times (Maher & Pezzotti, 2017). Though the giallo film is more often viewed from within exploitation horror cinema than from within the group crime films (Koven, 2010), it too was fashioned as a lense through which to view the culture for which and out of which it was initially made. Yet, the giallo, established as ambivalent, cannot commit to its relationship with Italian-ness either. When gialli are set in Italy it may alternately promote Italian-ness through excessive inclusion of tourist traps as eye candy, or erase Italian-ness by using European or rural locations to confuse the setting (Needham, 2002).

The giallo that superficially embraces its Italian-ness by locating action at tourist hotspots may also cast a foreign tourist as the center of its story and use those same tourist hotspots as places of murder. The foreign influence of giallo literature and the xenophilia it encouraged is often revisited in giallo cinema where, reflecting the traveling obsession of the new European ‘jet-set,’ tourism and foreignness create a point of contrast against which Italian-ness can be viewed at a new angle (Koven, 2006; Needham, 2002). Though considered to be for local consumption, many well regarded gialli were products of international co-productions (Heller-Nicholas, 2012), further emphasizing the national identity duality at play in the films. The tension of alternating Italian-ness, foreignness, and Italian-ness as reflected in the foreign adds to a common theme of questionable vision and perception, where nothing is as it appears (Hutchings, 2009; Brown, 2012).

Essence of Giallo

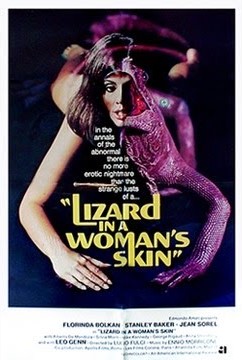

In addition to the tension of Italian-ness juxtaposed with that of otherness, there are commonalities to giallo films that have shaped audience perceptions of what constitutes a giallo (Needham,2002). A certain amount of formula could beneficially give the audience a firm footing to enjoy the visual, graphic, violent, and ephemeral nature of the films (Koven, 2006). The character of the amateur detective or everyman hero, the means by which the killer is discovered (Brown, 2012; Koven, 2006), also directly involves the audience by giving viewers a portal through which to project themselves on the action. The killer will be disguised, typically in black with black gloves. The disguise, as well as the closed point of view shots, help to obfuscate the killer’s real identity, giving the audience yet another portal through which to involve themselves in the action. The killer himself may be subject to some identity and/or gender confusion, perhaps as a result of a childhood trauma that most probably involved sex or his parents or both (Koven, 2010; Koven, 2006; Smith, 1999). The victims are often women, however, there is also a monstrosity to the female characters (Heller-Nicholas, 2012; Koven, 2006). Many of them are in therapy, have been in therapy or told they need it (Needham, 2002). It is important to note that female monstrosity in these movies does not necessarily equate to a female killer. Stefania Casini, an actress in Suspiria and Solamente nero (The Bloodstained Shadow), would say that horror “films are made mostly by men … who see in a woman the image of every kind of perversion, the image of she who caused his eternal separation from Earthly Paradise. It’s because men don’t know women that they weave around them countless significances and fears (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996 p 33).” Propelled by sexual revolution, these fears and perceived perversions manifesting themselves in a female monster can even be seen in the titles of some notable gialli: Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin), Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh (The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh), La Morte cammina con i tacchi alti (Death Walks in High Heels).

In addition to the tension of Italian-ness juxtaposed with that of otherness, there are commonalities to giallo films that have shaped audience perceptions of what constitutes a giallo (Needham,2002). A certain amount of formula could beneficially give the audience a firm footing to enjoy the visual, graphic, violent, and ephemeral nature of the films (Koven, 2006). The character of the amateur detective or everyman hero, the means by which the killer is discovered (Brown, 2012; Koven, 2006), also directly involves the audience by giving viewers a portal through which to project themselves on the action. The killer will be disguised, typically in black with black gloves. The disguise, as well as the closed point of view shots, help to obfuscate the killer’s real identity, giving the audience yet another portal through which to involve themselves in the action. The killer himself may be subject to some identity and/or gender confusion, perhaps as a result of a childhood trauma that most probably involved sex or his parents or both (Koven, 2010; Koven, 2006; Smith, 1999). The victims are often women, however, there is also a monstrosity to the female characters (Heller-Nicholas, 2012; Koven, 2006). Many of them are in therapy, have been in therapy or told they need it (Needham, 2002). It is important to note that female monstrosity in these movies does not necessarily equate to a female killer. Stefania Casini, an actress in Suspiria and Solamente nero (The Bloodstained Shadow), would say that horror “films are made mostly by men … who see in a woman the image of every kind of perversion, the image of she who caused his eternal separation from Earthly Paradise. It’s because men don’t know women that they weave around them countless significances and fears (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996 p 33).” Propelled by sexual revolution, these fears and perceived perversions manifesting themselves in a female monster can even be seen in the titles of some notable gialli: Una lucertola con la pelle di donna (A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin), Lo strano vizio della Signora Wardh (The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh), La Morte cammina con i tacchi alti (Death Walks in High Heels).

Yet, nothing is really as it seems within a giallo. The films play with vision and perception, unreliable narratives and witnesses, restricted views, darkness and shadow, so that every clue to the killer’s real identity becomes a question instead of an answer (Heller-Nicholas, 2012; Koven, 2006; Needham, 2002). Many gialli use “garish, sometimes psychedelic colored lights” to emphasize and juxtapose the darkness (Schmidt, 2015 p1). This further obscures, captivates, and distracts the vision of the characters and viewers alike. Some gialli capitalize on this play with vision and perception by making a primary target of a victim’s ability to see. The killer in Gatti rossi in un labirinto di vetro (Eyeball) gouges out the eyes of his victims. In Dario Argento’s Opera the victim’s eyes are forced open with needles so that she witnesses the deaths of her friends and fellow cast members as the killer wishes her to see them. One of the amateur detectives in another Argento film, Il gatto a nove code (The Cat o’ Nine Tails) is blind and relies on the perception of a child to visualize pieces of the mystery surrounding him. Primary characters are also subject to hallucinations, prophetic and tortured dreams, or, perhaps, drug altered perception, as in La morte accarezza a mezzanotte (Death Walks at Midnight), where a model/celebrity witnesses a murder while under the influence of drugs and the questionable intentions of her photographer. This compromised ability for the characters to comprehend the scenes around them is elevated by a current of superstition, folk belief and urban legend which can lead to seemingly supernatural events. However, gialli typically have a human mover (Koven, 2006), and the supernatural is explained away, relegated to misdirection. A notable deviant of this commonality, Deep Red, bridges the gap between Italian Gothic and giallo by incorporating truly supernatural elements that are not rationally explained away (Brown, 2012). However, these elements are peripheral to the primary story of detective and killer, who both are and remain, as in other gialli, completely human.

Conclusion

The human mover, mystery, and detective elements of a giallo may be a few of the most reliable, though not very unique, characteristics for defining what it is that makes a giallo a giallo. The other primary characteristics discussed so far, that of foreignness and the ‘other,’ along with compromised vision and perception help to undermine a true definition of the films, in that everything is not as it seems. With this in mind, the definition of a giallo film may be simply a film that feels like a giallo film. This may be in conflict with scholarly definitions of the giallo which set it within a certain time and geographic space, but it is in support of the concept proposed by Mikel Koven of giallo as a filone, or a trend, a vein, or cycle of something (2006). A giallo is a giallo then because it somehow feels like a giallo that came before. In this way the possibilities for what could be classed as a giallo become endless. This feeling of a giallo is prominent in the interviews conducted by Palmerini & Mistretta of directors, actors, and primary movers of Italian fantasy cinema. Lucio Fulci, director, writer, and actor, would say that how you are influenced by the genre “depends on your own imagination.” Daria Nicolodi, actress and writer, emphasized the emotional response inspired by horror films that no other genre manages to impart. According to Romano Scavolini, director, “horror is the most cinematic of all film categories. It’s an abstraction which touches every aspect of our daily lives and which allows us to cross the threshold of reality. It’s a genre which has no physical or temporal limitations and is impossible to control (Palmerini & Mistretta, 1996 p147).”

While linking the cinematic giallo with its literary forebear and counterpart provides some idea of what a giallo film may be, it also provides more flexibility for classing a film among the collection of films that have been described as cinematic gialli. If the literary giallo has a fluidity that allowed it to evolve and remain relevant when other literary genres did not, then would not the cinematic giallo inherit some of that very fluidity and resistance to proscribed description and formula? If, through the literature, an entire genre could be remade by one word and that word become the term for any and all mystery and intrigue, would not the cinematic embodiments of that term also be as timeless and pervasive? The giallo film’s own exploration of unreliable perception, gender and identity confusion may have created a class of films that, though sharing similar traits, is not always what it seems. Unlike the mystery novel that Raymond Chandler described, with a spirit of detachment that solved its own problems and minded it’s own business (1944), the giallo film unabashedly involves the audience. It challenges the viewer to see themselves in both the amateur everyman hero and in the mysterious killer; to look violence and murder in the face, embrace the human subsoil, and ruminate for a short while on the equally satisfying yens for freedom, taboo, and justice.

References

- Bolondi, E. (2017) Il Romanzo Giallo Italiano: un fenomeno letterario di successo. SoloLibri.net retrieved: https://www.sololibri.net/successo-romanzo-giallo-italiano.html

- Brown, Keith H. (2012) Gothic/Giallo/Genre: hybrid images in Italian horror cinema, 1956-82. Ilha do Desterro. 0(62): 173-194 https://doaj.org/article/244da972e55643059be3ec3012cf6e34

- Burnes, J. (2011) Founding Fathers: Giorgio Scerbanenco. in G. Pieri eds. Italian Crime Fiction. University of Wales Press.

- Chandler, R. (1944) The Simple Art of Murder. Atlantic Monthly. December

- Cicioni, Mirna. (2013) Giuliana Pieri ed.: Italian Crime Fiction. Italica. 90(2) 312. book review

- De Angelis, Augusto (1980) Conferenza sul giallo (in tempi neri), La Lettura: Rivista Mensile 47: 27-44

- Dunnet, J. (2011) The Emergence of a New Literary Genre in Interwar Italy. in G. Pieri eds. Italian Crime Fiction. University of Wales Press.

- Eckert, Elgin (2016) Barbara Pezzotti, Politics and Society in Italian Crime Fiction: An Historical Overview. Forum Italicum. 50(3): 1249. book review http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0014585816678800

- Heller-Nicholas, A (2012) Cannibals and Other Impossible Bodies: Il Profumo Della Signora In Nero and the Giallo Film. Scopte: An Online Journal of Film and Television Studies. issue 22. Februrary. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/scope/documents/2012/february-2012/heller-nicholas.pdf

- Hutchings, Peter (2009) “I’m the Girl He Wants to Kill:” The ‘Women in Peril’ Thriller in 1970s Britain. Visual Culture in Britain. 10 (1) 53-69.

- Koven, M. J. (2006) La Dolce Morte: vernacular cinema and the italian giallo film. Scarecrow Press: Lanham, Maryland.

- Koven, Mikel J. (2010) The Jewish giallo, or What’s a nice Jewish motif like you doing in a movie like this? in Magdalena Waligórska and Sophie Wagenhofer (eds.) Cultural Representation of Jewishness at the Turn of the 21st Century. Florence: European University Institute. http://cadmus.eui.eu/dspace/handle/1814/14045

- Maher, Brigit. (2016) ‘La dolce vita’ meets ‘the nature of evil’: the paratextual positioning of Italian crime fiction in English translation. The Translator. 22(2) 176- http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13556509.2016.1184879

- Maher, Brigid & Pezzotti, Barbara (2017) Hybridity in Giallo: The Fruitful Marriage Between Italian Crime Fiction and Theatre, Literary Geographies, and Historical and Literary Fiction. Quaderni d’italianistica. 37: 9-16

- Needham, Gary (2002) Playing with Genre: An Introduction to the Italian Giallo. Kenoeye. 2(11) no pagination http://www.kinoeye.org/02/11/needham11.php

- Palmerini, Luca M & Mistretta, Gaetano (1996) Spaghetti Nightmares: Italian Fantasy-Horrors as Seen Through the Eyes of Their Protagonists. Fantasma Books: Key West, FL.

- Pieri, G. (2011) Italian Crime Fiction. University of Wales Press.

- Santovetti, Olivia (2012) Italian Crime Fiction. Journal of European Studies. 42(3): 297- http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0047244112449968b book review

- Sciascia, Leonardo,‘ Appunti sul “giallo”’, Nuova Corrente, 1 (June 1954), 23- 34

- Schmidt, Richard. (2015) Giallo Meltdown: A Moviethon Diary. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Smith, A. L. (1999) Blood and Black Lace: The Definitive Guide to Italian Sex and Horror Movies. Stray Cat Publishing: Cornwall, London.

- Somigli, Luca (2005) The realism of detective fiction: Augusto de Angelis, theorist of the italian giallo. Symposium. 59(2): 70- http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.3200/SYMP.59.2.70-83

- Van Dine, S. S. (1928) Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories. The American Magazine. September

- Weller, Philip (2012) Italian Crime Fiction: A Barbarian Perspective. Linguae &. Rivista di Lingue e Culture Moderne. 11(1-2): 119-132 https://doaj.org/article/b754d74c398347f9acb7ca3b43b8b6a7

- Wikipedia (2018) Ossessione. Retrieved: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ossessione

- Wikipedia Italia (2018) Storia del Giallo. Retrieved: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Storia_del_giallo

- Wilson, Rita (2017) Local Colour: Investigating Social Transformations in Transcultural Crime Fiction. Quaderni d’italianistica. 37: 9-16 http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=hus&AN=125126951&site=ehost-live